IP Dragon was attending yesterday evening the very inspiring lecture of Professor David Llewelyn at the University of Hong Kong, about the importance of intellectual property rights for not only experts, but everybody.

IP Dragon was attending yesterday evening the very inspiring lecture of Professor David Llewelyn at the University of Hong Kong, about the importance of intellectual property rights for not only experts, but everybody.

Professor Llewelyn made clear that the lecture was a public lecture meant for non-experts; the normal consumers; and put experts and expertise in perspective. He quoted Lord Denning that in the dictionary for example the word barrister comes directly after bankrupt and just before bastard. “IP needs to be understood, especially in this part of the world [referrring to Asia] by many constituencies that don’t relate to each other. Patent people can only think about patents. Trademark people about trademarks etc.” Professor Llewelyn was determined to speak only about the good things of intellectual property rights, so not about counterfeiting, pirating and the pressure of the developed countries on local developing governement officials.

Professor Llewelyn was referring to patent in all its meanings. The sentence: “It is patent” for example means “It’s available.” He was recalling Huawei who overtook the number one position of the company with the most patents from Panasonic. Professor Llewelyn was going to say only good things about IPRs, but as a good friend of IPRs, he critisised IPRs starting with patents: most were vanity publishing.

Then he was filleting the quality of some Hong Kong patents, and after a pit stop to the “stepsister of patents’: trade secrets, he was off to trademarks. Professor Llewelyn told about the dispute between Jiangyou in Sichuan province and Anlu in Hubei province, who both claim their city as the hometown of the famous poet from the Tang dynasty called Li Bai.Jiangyou was not amused when they became familiar with a commercial on China Central Television (CCTV) that identified Anlu as the hometown of Li Bai. According to the South China Morning Post, Xinhua reported that the Jiangyou had registered the trademark “the Hometown of Li Bai, the City of Chinese Poems” in 2003. Therefore Anlu’s commercial allegedly violated the trademark. Never mind that Jiangyou nor Anlu was the birthplace of the ancient poet, which was small town in what now is Kyrgyzstan, as the South China Morning Post mentioned.

Professor Llewelyn urged companies to think ahead: Chinese computer maker wanted to expand abroad, but they forsaw problems with the trademark legend that was already trademarked in many countries. Therefore they decided to change their name into Lenovo, which is distinctive enough and not descriptive or laudatory. Professor Llewelyn pointed out the possibility that trademarks could be used in an unfair manner, to bully other companies into submissiveness. As an example he gave KFC who sued an neighbourhood restaurant for infringement of the use of the trademarked term ‘family feast’. He draw the history of Hong Kong artist Michael Lau and his relation to trademarks/bootlegs.

Genericide was discusses as well. Escalator, tabloid were generic names, but not roller blades.

Then the subject changed to geographical indications. The danger always lurks that two states, such as Indonesia and Malaysia start fighting over a term for food: such as who owns Nasi Lemak.

The territorial nature of intellectual property rights were discussed.

Copyrights you obtain for nothing; but the flipside is that they only forbid the right to copy; and another challenge is the digital era, as you can read in “Free”, the book by Chris Anderson. Professor Llewelyn referred to China’s threats to sue over fake terracotta warriors, as a subject that is outside the scope of copyrights. Professor Llewelyn compared it with the Egyptians that want to copyright the pyramids.

Normal copyrights are the life of the creator plus 50 years (China, which is TRIPs standard) or 70 years (many countries). In the UK there is special legislation for the play ‘Peter Pan, or the boy who whould not grow up’ to give it perpetual copyright in order to finance the Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Among intellectual property rights are strange creatures, such as database rights.

And many new players such as UNESCO are getting in to the act as well to protect rather exotic new intellectual property rights.

Intellectual property rights are liabilities, unless you do something with them. Commercialisation is getting more popular.

There are only five countries in the world with a net balance of payment: US, UK, Japan, Sweden and France. China has taken this well into account and makes sure that it is self innovating in order to avoid to pay too much royalities.

When one analyses intellectual property rights one can do it from many perspectives. An academic (access to information) has another perspective than an author of a book (control of information). Professor Llewelyn told about a student in Beijing who asked him to sign a copy of his book that was “better bound than [his publisher] Sweet & Maxwell.”

Anti-competition law is becoming more important in intellectual property right law. Professor Llewelyn advocates a balance between extremes.

A development we must take an eye on is according to Llewelyn developing countries, such as India, that demand green technology of the developed world.

Hong Kong lawyers were always more interested in transactions of IPRs, registering etc. than in advising them about how to best exploit their IPRs.

In 60 minutes Professor Llewelyn covered a lot of ground. Ron Yu asked him whether IPRs are not getting too complicated for the average consumer. Professor Llewelyn answered: “Yes and also too complicated for the experts.”

IP Dragon asked him about his take on the new international IPR forum ACTA, and whether it would be a threat to forums such as WIPO and WTO’s TRIPs? Professor Llewelyn answered that he does not like the new forum, it will be more complicated.

So there will be a great need for people who can explain and illuminate these complicated issues in an inspiring way in the future, just like Professor Llewelyn.

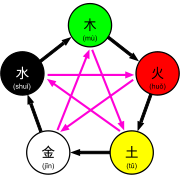

Last month (October 22nd 2009) The Economist had a special report about the relationship between China and the US. In the article ‘The price of cleanliness’ the circular reasoning is pointed out that makes solving the environmental challenge in China very difficult:

Last month (October 22nd 2009) The Economist had a special report about the relationship between China and the US. In the article ‘The price of cleanliness’ the circular reasoning is pointed out that makes solving the environmental challenge in China very difficult: